The deadlift. Semantics have always prevailed in the past when attempting to define the perfect deadlift. So let’s take this from a dissimilar line of attack shall we?

To avoid paralysis by analysis – I will systematically dissect the deadlift, focusing on what is justly important, and weeding out the immaterial and insignificant nuances.

Let’s get right down to it, by clearing up what I make out to be frequently recurring topics of debate when it comes to the deadlift.

1. Is the deadlift a hinge or a squat?

It took me a while to finally come around and say this, but who the hell cares! There is clearly both a knee dominant and a hip dominant component to the deadlift.

How do YOU define a squat? Personally, I would say any hip hinging and knee flexion movement coupled with an angled tibia (ankle flexion) is a squat, but that’s just me. There is no accurately defined set of standards as to what is a squat and what is a deadlift. And being a guy who believes there should be a set of clear standards for everything, I have found this to be quite frustrating – but at the end of the day, does the classification really matter? No, execution does.

2. Ok, fair enough. So how low should you set your hips?

Somewhere above your knees but below your shoulders – everyone is an individual (mechanically speaking), therefore everyone’s set up will look slightly different.

3. Shins against the bar?

Not initially. The bar should be set up so that it roughly dissects your foot in half, allowing for an ample amount of dorsiflexion in order for you to “wedge” yourself between the weight.

4. Look up, down, or at the horizon?

No. This is particularly important, and I will tell you why shortly

5. Chest over or behind the bar?

Bar should be under your scapula/shoulder blades – so yes, shoulders/chest may be over the bar.

Those are five, but undoubtedly not all, of the most universally debated topics in regards to the king of primitive movements. If you have any other questions that I don’t directly address in the next section, please post them in the comment section or over at the Colloquium. Now let’s get down to what really matters when deadlifting…

Neck/Head position – I have talked and worked with deadlifting “experts” since I began lifting my sophomore year of high school, and the only consistent thing about how each of them approached head and neck position in the deadlift was inconsistency. Working with a professional powerlifter during my early undergrad years, there was one and only one acceptable way to set up your head and neck position for the deadlift– and that was to look up and maintain cervical extension in order to take advantage of our extensor reflex. The body follows the head right? Sort of…

Before I get into why that’s “less than optimal”, I then had to reprogram myself to fix my gaze on the horizon when I became an RKC. While I unquestionably felt this helped resolved a lot of low back pain and neck stiffness that I was dealing with, it did not completely alleviate all my symptoms.

Then I met Dr. Charlie Weingroff, who introduced me to the concept of “packing in the neck”. Now before I go on to tell you why this practice is “right”, I’m going to provide you with some soft science as to why the practice of cervical extension is “wrong” (quotation marks for CYA purposes)…

1. What happens in the C-spine, trickles down the rest of the spine. Whereas, cervical extension will lead to excessive extension throughout the rest of your spine – most importantly your lumbar spine (resulting in hyperlordosis). Now why is this a dilemma? Because one of the primary benefits of a good deadlift is the development of authentic lumbar stability – now this is achieved when pulling from, well… a position of authentic stability (neutral spine – maintaining natural lordotic and kyphotic curvature of the spine), rather than a position of structural stability (hyperlordosis/bony approximity). Who would have guessed?

2. As renown PT and strength coach Dr. Charlie Weingroff has stated, hyperlordosis and an anterior pelvic tilt results in bony approximity (bones moving closer together), which in turn inhibits your inner core stabilizers (transverse abdominus, multifidus, diaphram, etc) because your body has the hold up it needs from structural bony support.

3. Cervical extension loads the neck and inhibits deep neck flexors. This was exactly why I was experiencing such an annoying amount of tightness and discomfort in my neck after my heavy deadlift days. When pulling or swinging with cervical extension, the neck is now put under load- which leads to the inhibition of your deep neck flexors (sternocleidomastoid and scalenes). These muscles are designed for rapid changes in head position, not for supporting large amounts of weight. So unless you want weighty masses hanging off your C-4/C-5 region, which from experience I find to be quite discomforting, then cease to lift with C-spine extension.

To learn how to properly pack your neck in, head over to this page to review Dr. Weingroff’s extensive post on this subject.

Foot position – We started at the head, now let’s take a look at the feet, then work our way up to the middle. And just to clarify, I am talking about the conventional deadlift, not sumo, or any other style.

So, for just about everyone, feet should be placed no wider than shoulder width apart and pointed straight ahead. That’s right, no duck stance. Poor mobility is not an excuse. The deadlift is a lift requiring an ample amount of requisite mobility. If you do not have the requisite mobility, then do not deadlift. Work on your mobility.

Knee issues are often a result of poor hip mobility, specifically internal hip rotation. As you descend into a squat pattern, your femur is designed to internally/medial rotate in order to maintain pelvis position. When lacking internal hip rotation mobility, the compensatory action is often a valgus and/or arch collapse and the (bowing in) destruction of your knee joint. Pulling from a wider stance/external rotation is only avoiding the problem. Work instead to correct/improve your restrictions before proceeding to the deadlift.

Further more, feet pointed straight ahead will help to pre-stretch abductors and get them beautiful gluteals firing a bit more.

Back Position – I would like to confidently assume that the most important aspect in regards to back position for the deadlift is to maintain our natural lordotic and kyphotic curv

ature of the spine. But you know what they say about those who assume…

Let’s take this one form the T-spine (specifically the scapulo-throacic joint). Aside from alignment neutrality, we want scapular abduction and depression before we initiate our pull. Meaning we want to pull our shoulder blades down and together, and to employ our lats (imagine trying to pinching something between your arm pits. This will assist with the transfer of force and to help prevent the bar from getting away from us as we pull. As a matter of fact, it is not uncommon for one to bloody up their shins when deadlifting. Now I personally think that is taking things a little too far, but you it gives you an idea that you should visualize pulling the bar up and towards you, rather than just up.

Heading down to the lumbar – again we want neutrality. No flexion or hyperlordosis (excessive arching). This is the region where stability is of the utmost significance.

Pelvis – I hate when I sound like a broken record, but the magnitude of this subject matter demands reiteration. Neutral, neutral, neutral. No anterior or posterior pelvic tilt please.

Breathing – Diaphramatic.

Requisite Mobility – As I stated beforehand, the deadlift requires a requisite amount of mobility in order to be performed properly.

1. Ankle Mobility – You need a sufficient amount of dorsiflexion in order to wedge yourself into position. Poor ankle mobility is often inappropriately compensated for by either elevating the heels/leaning forward, or relying too heavily on hip extension.

2. Hip Mobility – This is a biggie. Poor hip mobility leads to some rather tragic compensatory actions, the most dangerous being lumbar flexion. Your body is not stupid, it knows what it needs to do, and it will do what it has to in ordr to get the job done. So if hip mobility (flexion) is restricted, your body will mimic that pattern often times through lumbar flexion.

Requisite Stability – Mobility and stability are two sides of the same coin. Both are required in plentiful amounts in order to perform a safe, strong deadlift.

1. Hip Stability – Yes, your hips need to be stable as well as mobile! Add to my point above about how hip immobility can destroy your knees, hip instability is by the same token just as dangerous. Your hip needs to be able to prevent adduction in order to prevent stress on the knees. If your abductors and external hip rotators are too weak/unstable, then this must be corrected before ever attempting to engage in a heavy deadlift. Spend plenty time strengthening your glute medius. Don’t wait until after reconstructive surgery to pay attention to this…

2. Lumbar Stability – I’m done beating a dead horse… Long. Tall. Spine.

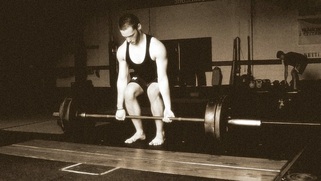

Enough talk. Here’s a video of a “better” deadlift. I know that the title says perfect – but that’s because I like catchy youtube titles. Perfect is just not going to happen. You can only work on being better.

PS – I covered a lot, but not everything. Post your questions below or over at the Colloquium

Chris Foehl Snatch Test

A few tweaks regarding hip snap and lock out and he’s golden, but overall, not too shabby for an old man ;p and I’m incredibly proud of his progress.