Seneca and the Problem of Pain

That God allows suffering into the world to deliver some outweighing benefit is indeed a distinct, but not exclusively, Christian idea. Many philosophies and religious systems have thought something similar. This is interesting for a couple of reasons. First, it shows the Christian response to the problem of pain is by no means unreasonable or ad hoc but is drawing (and expanding) upon a rather venerable and longstanding philosophical tradition. Second, it shows that people from different backgrounds have all been able – upon sufficient reflection – to see past the initial terror of suffering and realize there are potentially major benefits to be had in our response to it, and, more specifically, benefits that might otherwise not had been available apart from the occurrence of suffering and evil.

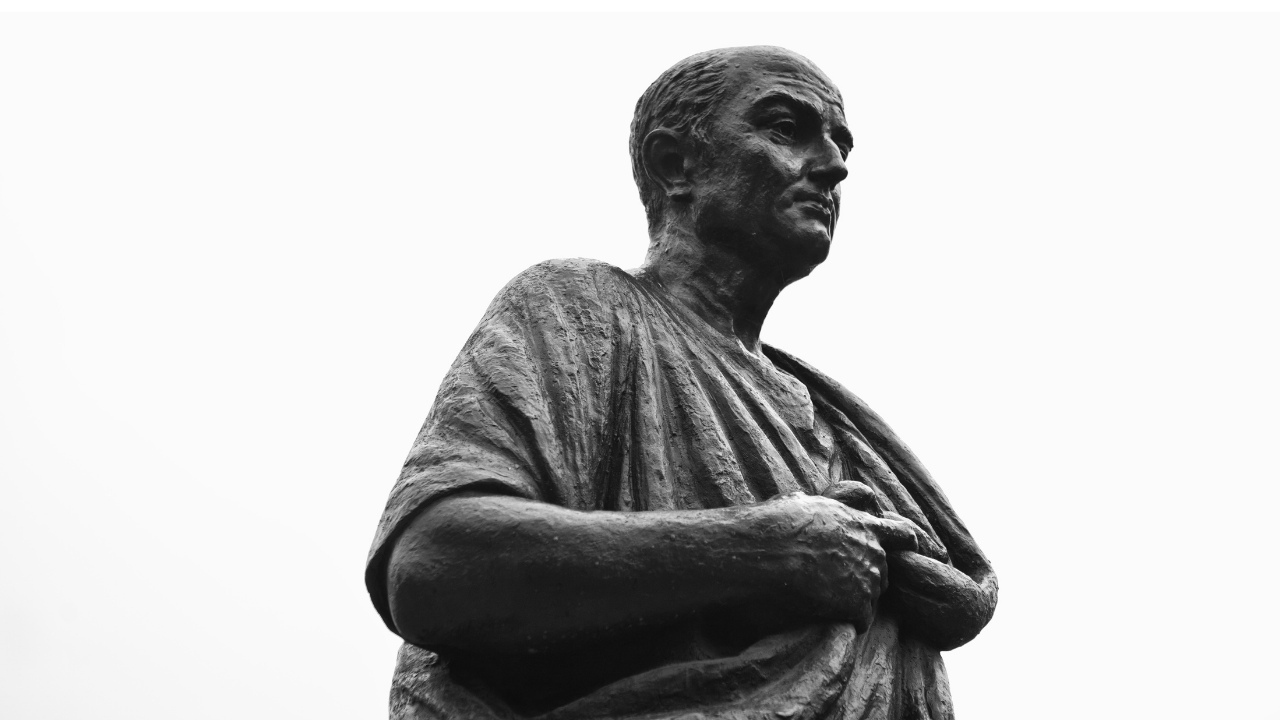

The stoic philosophy Seneca is just one example, and his articulation of his response of the problem of pain can be found in On Providence. In response to Lucilius, he is answering the ever-common question of why many evils befall good men if the world is governed by providence (i.e. God). While I do not follow Seneca in his every line of thought on this issue, there are insights we can glean from this Stoic crustacean, some of them unique, and others surprising.

His strongest response is this, “It is not possible that any evil can befall a good man. Opposites cannot combine… I do not maintain that he is insensible to externals, but that he overcomes them; unperturbed and serene, and rises to meet every sally. All diversity he regards as exercise.”

Seneca is obviously being rhetorical, here. Bad things really do happen to good people, so what he’s emphasizing (I think) is the importance of our response to any such unfortunate situation, and how adversity can be turned ultimately to strength. And such is a general theme I think many (if not most) people not only agree with but see as especially honorable and worth pursuing. It is why we celebrate those who overcome incredible hardships; it is why we call such people heroes.

“As my discourse proceeds, I shall show that what seems to be evils are not actually such.” And, indeed, much of the rest of Seneca’s essay makes that attempt, highlighting the admirable virtues and inestimable glory so many legendary figures accomplished through their stalwart perseverance in the face of suffering, from Socrates to Cato and so on.

The Christian can accept much of Seneca’s proposal, with the addition of a few philosophical distinctions. The privation account is necessary, of course, to preserve divine innocence. But also we do not want to say that evil things are not actually evil: they are, and so we shouldn’t want to look into the face of somebody who is suffering in a heap of agony, and say, “Come on! Haven’t you read Seneca? Cheer up! This is a good thing!” The point is merely that in every evil thing there is opportunity for some greater good.

Interestingly, Seneca also embraces the idea that evils which befall humanity may not just be for the individual, but the good of the whole. That is a thought worthy of many years reflection.

I may add more later. In the meantime, I’d recommend (if this topic interests you) my recent interview with Dr. Torre on the mystery of evil and the goodness of God.

The Mystery of Evil, Providence, and Human Freedom with Dr. Michael Torre