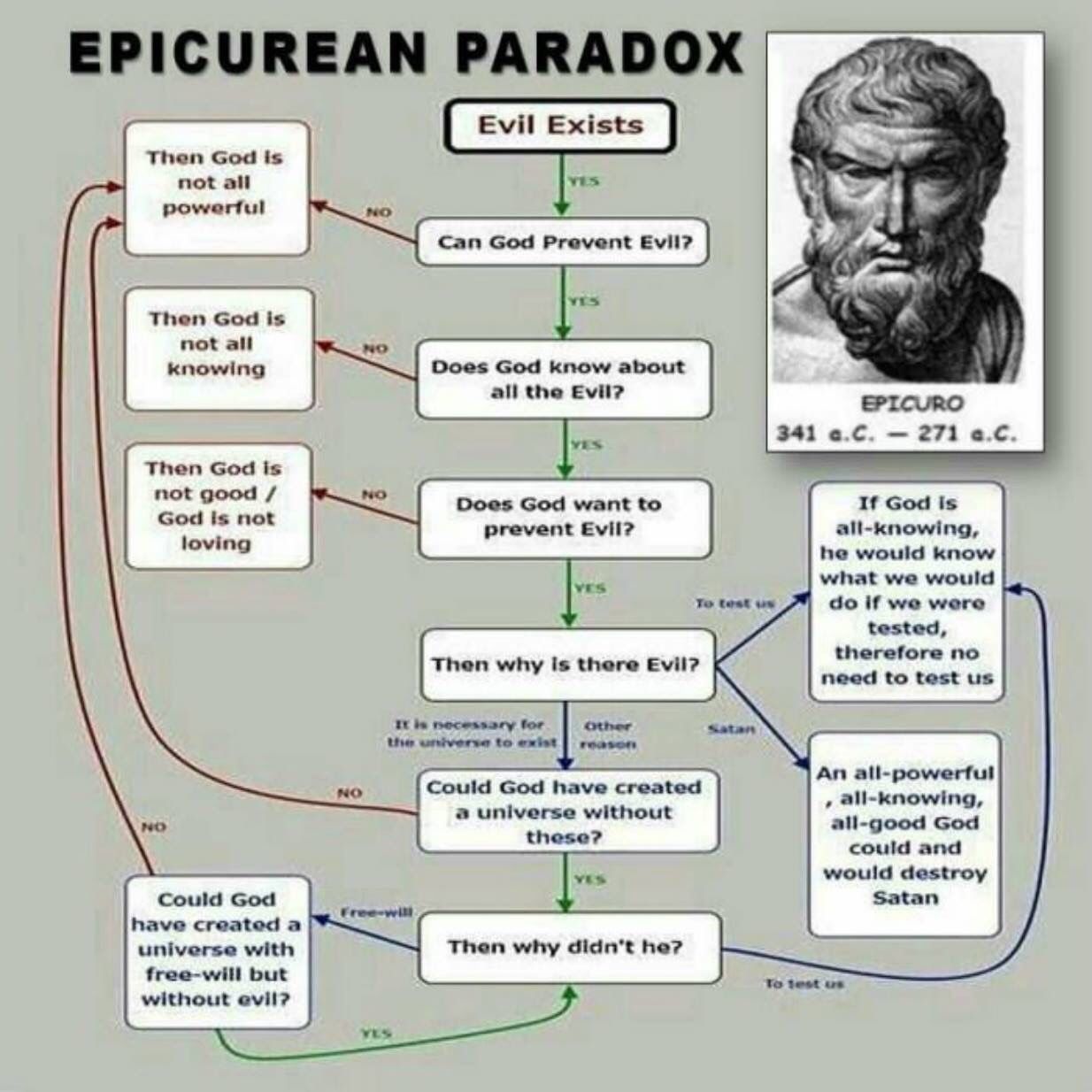

Philosophically, the Epicurean Paradox (i.e. problem of evil) can be resolved by firmly embracing the common Augustinian-Thomistic retort that from every evil God is “omnipotent enough” to draw some greater good, which alleviates any alleged contradiction between God (classically understood as omni-attributed: all powerful, knowing, and good) and evil; and thereby shifts the burden of proof to the skeptic to prove the impossibility thereof; a burden which has surely never been sustained. Thus, the theist might respond that given what is already clear — say, philosophical arguments for classical theism — we can use that illumination of reason to cast light on whatever remains mysterious — say, why any particular evil situation attains. We can, to put it differently, use our knowledge of God as all-loving and all-powerful to confidently infer that, though we often do not see reasons for this or that instance of suffering or evil, we can see that there must be reasons, however far removed they are from our finite, limited perspective. (Also, should it surprise us that God has reasons we cannot see? Given the infinite chasm between finite being and the unrestricted absolute, mysteries, to my mind, are not really surprising at all.)

Granted, people may find the philosophical response emotionally unsatisfying, but there only a simple reminder is in order: the task of the philosopher is to appeal to reason rather than emotion, and so it is simply not a worthwhile rebuttal to call this response unfeeling: it isn’t trying to be tender; it is only trying to be correct. And, for whatever else it’s worth, there may be some goods worth aiming at — forgiveness, empathy, compassion, acts of heroism, the atonement, etc — that may otherwise be impossible or severely diminished had God created a so-called perfect world from the very beginning, if (granting) such a world is metaphysically possible in the first place.

Quickly, there’s another element of this flow-chart every Christian should take issue with, and that is God “testing” us. So far as I’m aware, no aspect of Christian theology, and certainly not Catholic theology, has ever thought of this life as a mere moral testing ground, whatever that means. If anything, God wishes to form us, perfect us, and bring us freely to our ultimate and highest end (hence why God offers sufficient grace for all to be saved), given the unfortunate situation we find ourselves in regarding original sin. The notion of being created simply to be morally tested strikes me not only as an uninformed caricature of Christianity but probably the heresy of pelagianism; and, even apart from Christianity, is by no means a serious criticism of theism outright.

As for Satan, God loves even the devil (God, after all, creates in virtue of His eternal love; and his act of love, we must remember, just is his act of creation), and wishes not the devil’s destruction; but, as with any other fallible free being, allows Satan to reject God’s love if he so chooses, and though the devil undoubtedly wreaks havoc, God, again, in his eternal wisdom and providence, is able to draw some greater good from whatever mess the Wicked One makes. So, to say that God *would* destroy Satan is not only challengeable, but decidedly false.

Also problematic is the idea that *evil exists* without qualification. For this assertion overlooks an important philosophical tradition, one which ultimately oriented St. Augustine toward Christianity: the metaphysics of privation. Specifically, that evil is not something which maintains any “positive ontological status”, as it were, but rather like a hole in a sock, or my grandmother’s blindness, is something missing that is otherwise proper or perfective of some specific instance of being. In short, evil is a due good gone missing (a lack of order, harmony, symmetry, understanding, a limb, etc); or, stated differently, of something failing to meet our expectations. Thus, evil is not something created, but something absent, and so the metaphysics of privation provides further security of divine innocence, for if this account is correct, then God is in no way the cause of evil (specifically because evil is not something created). The question, then, must be re-formulated. Rather than why did God create evil (He didn’t; nor could he) the question is why did God create an imperfect world — a world, if you like, with holes in it — and to that we have already hinted at some plausible responses, which are sufficient to overcome any such logical formulations of the problem of evil.

Finally, consider this. To make sense of the notion of evil, there must first be some moral standard, of the way some things *ought* to be. If we deny the notion of an objective (read: mind-independent) moral standard, the problem of evil loses all its force as an argument against theism, and reduces to a matter of mere preference, to which we can say, “So what?” On the other hand, if we maintain the notion of a moral standard to reinvigorate the problem of evil, we can then ask which hypothesis — theism, or atheism — better predicts/explains not just a moral standard, but a moral community which is capable of reflecting upon that standard and attempting to conform their lives according to it. And so, it is upon a more profound — rather than merely superficial — understanding of evil, that evil itself is evidence for, rather than against, God’s existence.

Why so? Because on the theistic hypothesis (and especially classical theism) a moral standard is guaranteed in virtue of God being subsistent goodness itself: a supreme and perfect foundation, whose essence just is his existence, and who creates things with objective natures which tend toward some determinate effect(s) — i.e. their good. Humans, for example, in virtue of being rational animals, are perfected (in part) by truth; the highest of which is knowing God. Now, to avoid a common confusion: things aren’t good simply because of what God wills, neither does God will things simply because they are good. Rather, God is goodness itself (the form of the good, as Plato would have it) — the complete and awesome plentitude of being: who freely chooses to diffuse, and so allow us to participate in, his incredible goodness — and so we find a quite comfortable foundation for morality in classical theism, and it also seems quite reasonable to expect that God would see value in creating moral communities, and, naturally, granting God’s omnipotence, could easily bring such communities about.

Does atheism have similar predictive success? Please. It is not even close. While some philosophers wish to press the more aggressive position that a moral standard on atheism is metaphysically impossible (which I largely agree with, given, say, a materialist metaphysic), we needn’t make that forceful of a claim, because, whether impossible or not, it is surely far less probable that an atheistic worldview would generate a moral standard along with moral communities. Many atheists (especially materialists) are, in fact, nihilists, and see with inspiring clarity that particles (or any other fundamental physical simple, for that matter) simply could not, and indeed would not, add up to an objective moral standard — honestly, how could such a profound qualitative inversion, from the wholly amoral into the objectively moral, be even conceptually possible, let alone practically achievable? — and it only becomes even more extravagantly difficult to imagine how particles (or quarks or strings, etc) could arrange themselves to produce conscious, moral agents, capable of ethical reasoning, as well. Alternatively, it would seem to me that atheists who take a more platonic approach are really just veering (retreating?) toward theism, but still have considerable, if not insurmountable difficulty, explaining not only the emergence of moral communities, but also the causal connection (let alone imperative obligation) between moral communities and these supposedly abstract entities is supposed to operate. More technical, probabilistic formulations could be developed, but do we need them? I doubt it. At this point, the answer seems clear enough. While evil may initially seem to be at tension with the existence of God, upon deeper inspection and further contemplation, we see that evil itself points toward God’s existence, being better predicted and explained by theism than atheism. Thus, the problem of evil is not really a problem at all, philosophically speaking; rather, it is a theological mystery.

And this is good news, because in our commitment to theism that God is all-loving and all-good, so we can be assured that, though we do not see the reasons for many of the evils that befall our world, God does, and will bring those greater goods about. We can hope, and we can trust, in the goodness of our Lord.

– Pat

PS – See also…

The Mystery of Evil, Providence, and Human Freedom with Dr. Michael Torre