Believe it nor — believe it! — I recently had a (somewhat, sorta/kinda) productive exchange on a topic of religious nature on social media. They said this would never happen. They told me it was impossible and couldn’t be done. Well, feast your eyes on this, you unbelieving toad!

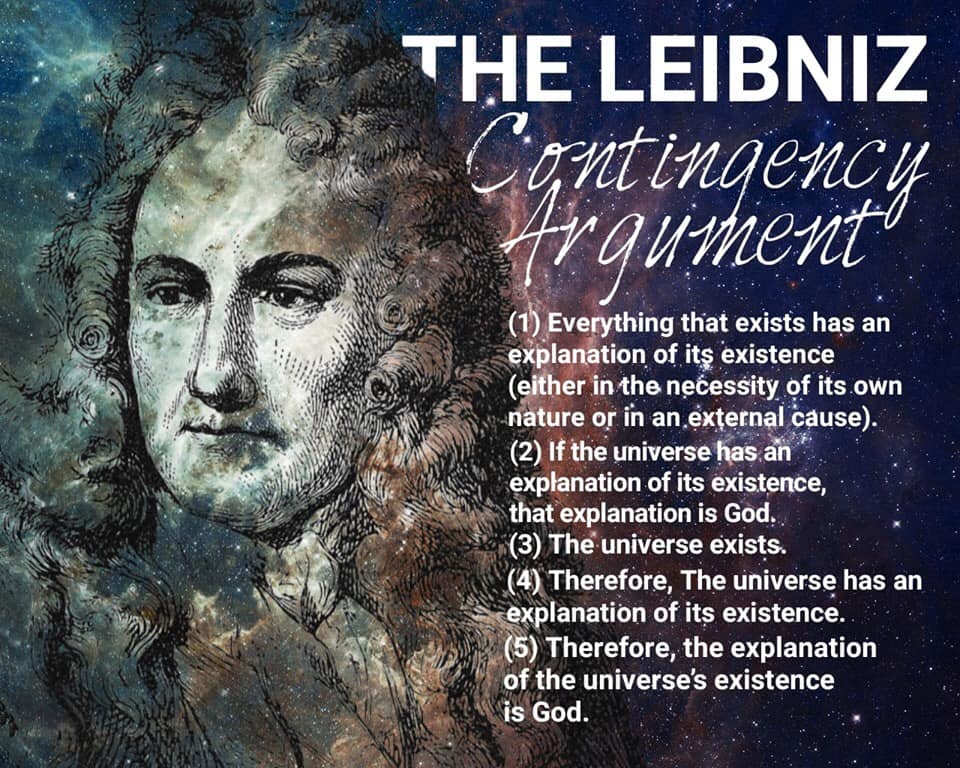

Somebody on my Facebook feed — not exactly a friend, let’s say more of an online acquaintance — does that sound like a friend? OK, a friend. Fine. He’s a friend. Anyway, this “friend” posted a meme of Leibniz’s argument from contingency for God’s existence. Let me first say that I find it a little bit odd/funny/peculiar/and frightening that we’re at such a point in meme culture where metaphysical demonstrations for God’s existence are now making the rounds. But hey, whatever gets the job done, I suppose.

So here it is.

To develop this argument at length would take (at least) a small book. So I’m not even going to attempt anything of the sort here. (If you’re interested in seeing such a demonstration, however, I have two beginning recommendations: 5 Proofs of The Existence of God by Dr. Ed Feser, or New Proofs for the Existence of God by Fr. Robert Spitzer. Both of these scholarly gentleman have been on my podcast, by the way. Feser here, and Fr. Spitzer here.). Rather, I’d like us to simply have a look at some of the objections posed by a commenter who, for whatever reason, be it the instigation of the Holy Spirit or simply boredom, I decided to engage.

I’m quoting him, now: “I like it. The problem with any successful proof of the existence of God, however, is that it does not prove the the existence of the Christian god. This proof proves the cause of the universe—though I’m sure there is plenty to discuss regarding the cause’s cause.”

I mentioned to this gentleman that I think he might be misunderstanding the argument. What the contingency argument shows, to the extent that it’s successful (and, indeed, you don’t need to believe it is successful to see the point I’m about to make) is the existence of a metaphysically necessary reality to explain any contingently existing state of affairs. So to the extent you conclude that God is this sole, ultimate reality, it then makes no sense to talk about God’s “causes.” That is literally asking what the cause of a metaphysically necessary, eternally existing uncaused reality is. And that just doesn’t work.

To his first point, I said he was absolutely correct. Arguments such as these do not directly demonstrate the existence of the Christian God. They only give us the so-called god of the philosopher. But that is, in my view, anyway, asking something of the argument that it was not originally meant achieve. This arguments, and arguments like it, do plenty of work by themselves — all of it admirable, in my estimation — even if they don’t answer every possible question we have about religion or God. For example, to the extent the argument from contingency succeeds (which, I believe it does), we are able to affirm a God that is the timeless, spaceless, immaterial, necessarily existing eternal reality that explains why anything exists instead of nothing. That is one Kiss concert of a conclusion, even if it doesn’t drive you to any particular religion right away. I mean, think of what the argument from contingency does. For one, it shows that atheism is false. It shows polytheism and pantheism are false, as well, since it gives us a conception of God that is radically distinct form the universe, simple, and non-composite — or in other words, one. (Clearly, I’m skipping the steps in the argument which demonstrate this, but that is beside the point; I’m merely attempting to show that if you believe the contingency argument succeeds, it actually tells us quite a bit more than the average online skeptic seems to be aware of, or is willing to admit.)

So even if we stopped there we have greatly narrowed the list of possibly true religions down to (pretty much) the great Abrahamic traditions. They would be the only sort of religions that would match up to what we can know about God philosophically, even if there are some remaining details to be filled in and questions to be asked. (For example: Does this God love us? Or has this God ever revealed himself?) So this argument has a profound winnowing effect. It doesn’t tell us what religion is true. But it does tell us what religions — and what other worldviews, like naturalism, physicalism, etc — are false. And why should that not be acknowledged? That seems a considerable achievement.

His retort to this, and I’m again quoting: “This argument does not prove the uncaused nature of the cause of the universe; nor is it trying—unless that is the purpose of the parenthetical aside.”

He also said: “The argument does not indicate any one god, familiar or unfamiliar to humanity. Perhaps there is a process of elimination possible, but ultimately a fruitless one. The god of the the philosopher is our ultimate given; we will never know beyond that in our mortal existence.”

And here is where his unfamiliarity with this type of argument becomes apparent. Because (to his first point) that is, in fact, exactly what this line of argument is attempting to show, specifically in this case through the principle of sufficient reason (Premise 1). To be fair — and I said this to him — it’s often hard to understand any argument, let alone a metaphysical demonstration for the existence of God, from a Facebook meme.

I offered the following alternative way of looking at it.

Quoting myself, now: “Conditioned realities exist. That is, there are things that exist that in order to exist require the fulfillment of conditions outside themselves. Think a dog or a planet or an octopus, etc. (Some philosophers call these contingent realities, like Liebniz, or caused causes, or what have you.). But could all of reality — whatever that happens to be — be collectively a conditioned reality? Well, it seems not. Because that’s just to say that all of reality is then awaiting the fulfillment of some set of conditions to come into existence. But since we’re talking about “all of reality”, there can be no such fulfillment of conditions, because there is nothing outside “all of reality.” To put it another way: all of reality would not exist, if all of reality were collectively a conditioned reality, which is as contradictory to experience as anything can get. Because all of reality does exist. So there seems to be a logical necessity in positing the existence of *at least* one unconditioned (or necessary) reality to explain why anything exists instead of nothing. That is, a reality that does not depend on the fulfillment of any conditions outside itself. A reality that is absolutely, metaphysically necessary; that exists and could not have failed to exist. And here we arrive at the notion of an eternally existing, uncaused cause of all reality.

Note: This conclusion would be true whether you posit a finite or infinite collection of conditioned realities. Trying to dump out of the argument with an infinite regress puts you in a similar snag. For example, if Thing A is dependent upon Thing B, is dependent upon Thing C, etc, etc, ad infinitum: you are really saying that the existence of Thing A is dependent upon +1 more set of conditions being fulfilled than can ever be met. That’s what infinite means. The unachievable. Therefore, by that logic, Thing A would never have come to exist. But Thing A does exist. So even if there were some infinite number of conditioned realities, there must still be the existence of at least one unconditioned reality standing in causal relation to these conditioned realities to explain why the infinite, contingent collection exists instead of nothing. Leibniz addresses this objection directly with his example of how, even if you had an infinite series of Geometry textbooks, one copied from another from infinity past, you’d still need something outside the text books to explain that infinite series instead of no series at all, or why it isn’t a series of, say, biology books, etc. Now, I believe there are still other problems with posting any sort of infinite causal series of events, but we can leave it at that for now since you seem to accept the argument so far as it goes, anyway.

From there, a person could take any number of paths to show how this reality is God (or, if you prefer, an unrestricted act of mentation/unembodied mind/what have you). Arguments have been given from the real distinction of essence/existence, or metaphysical simplicity, or modal intuitions, etc. It’s an interesting exercise and I think worth pursuing, if only because it shows how secure the conclusion is, since it can be reached in a number of different ways. Bernard Lonergan has an incredible (I think) epistemological version of this. But one can take a pretty quick shortcut as soon as you concede that all of physical reality is contingent, and how the only realities that could possibly stand outside of physical reality are 1) abstract objects or 2) an unembodied mind. But since abstracts objects don’t stand in causal relations (and it’s arguable whether they exist apart from minds to begin with), we’re left with accepting option number 2.

As to your final statement, about not being able to bridge the gap from the god of the philosopher to the God of Christianity — that is a strong claim. Do you have an argument for that? Why do you assume that is an impossible chasm to traverse?”

He also said in passing that God must have an explanation, as well. And that he does: he exists through a necessity of His own being. So God is not exempt from the principle of sufficient reason — rather, God satisfies the PSR — because the PSR states the explanation of something must be found either in an external cause (or set of conditions, or what have you), or a necessity of its own being.

Unfortunately, he never responded, and, to be honest, that bothered me. I was genuinely enjoying the exchange. And so I offered one final remark, like every other perfectly annoyance person online who just can’t let something go.

Once again, quoting myself (hey, somebody’s gotta do it.): “I hope you do not think I am being in anyway facetious. I spent a lot of time as an atheist, but once my study of philosophy got me to natural theology, I became convinced by the strength of many of these arguments. I then spent a fair amount of time as a religious pluralist, thinking, much like you, I suppose, that to the extent any religion is true, we probably will never know, or perhaps all are true, in a way. But then I took seriously the historical study of Christ, the evidence surrounding the resurrection, and arguments based on prior-probability like the kind Swinburne gives. None of these, of course, can prove the Resurrection directly, but they make the central claim of the Christian religion eerily likely, I think — certainly placed well within the bounds of rational belief. So whether that chasm is impossible to traverse will come down (again, I think) to just how much certainty you feel you need on the topic, and what you stand to gain or lose by not making a commitment one way or the other. Personally, I came to a point where I felt I had more than enough justification to make the commitment to living a deeply religious life by seeking God through Christ. And that turned out to be the best decision I ever made.”

I offered this comment to make my intentions clear and diffuse any potential animosity, which can so easily arise in online conversations like these. I’m not online to “win” arguments with people. I don’t have anything to prove in that department — I got that all out of my system when I was, like, 16 — nor have I found such contests to be overwhelmingly productive. But I am trying to make myself available to answer sincere questions and objections a person who is seeking may have. I did not get the impression this guy entered the thread to pick a fight, so I was interested in dialoguing with him and seeing what his hold ups were. If nothing else, I hope he gained a deeper appreciation of an argument he otherwise seemed to accept the conclusion of. Further, that he might consider seeing what evidence could possibly help him to cross that allegedly unsurpassable abyss — of getting form the god of the philosophers to the God of Christianity. And for that he is going to have to start asking sincere questions about Jesus Christ.

Having been down that road myself, I can tell you where it leads.

– Pat

Related Posts/Podcasts

You deserve a lot of credit for discussing religion on social media man. I’ve yet to see an intelligent conversation about it and it quickly breaks down into insults and illogical arguments. I don’t think it’s as bad as discussing U.S. politics on social media, but it’s not too far behind.

Unfortunately, you’re right. So I’m doing the best I can to un-poison the well.

I was unaware that there’s so many arguments and theories surrounding the existence of God. I’ve heard ones like the watchmaker’s argument but these tend to be simplistic (at least I think so). Good to read this and get a detailed explanation of the arguments behind the Leibniz Contingency Argument. I guess if you’re going on social media to discuss religion, you’d better know the arguments people will raise.